News & Updates

Why I Use My Voice: My Journey to Health Policy

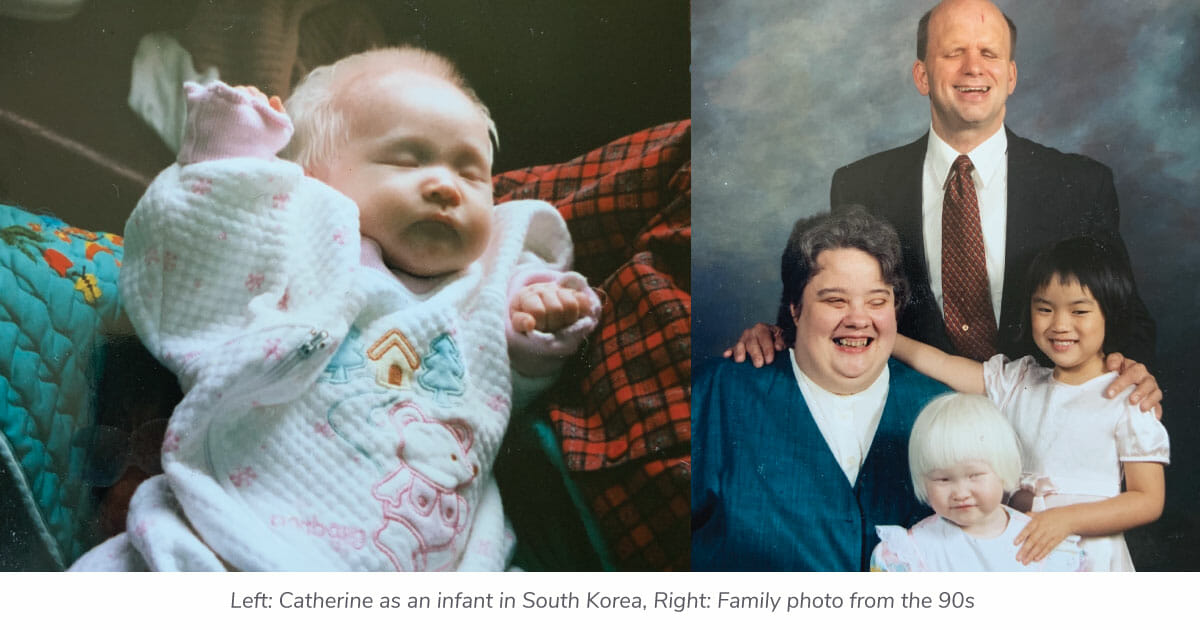

Twenty-five years ago I was born in South Korea with OCA1A albinism, which causes no pigment to show in my body, including my skin, hair, and eyes. Albinism is paired with vision loss and other eye problems, which has resulted in my legal blindness. About 7 months after I was born I was adopted by my parents Steve and Nadine Jacobson in Minnesota.

My parents are both completely blind. My father worked at 3M for 40+ years, and my mother was a social worker for the largest county in Minnesota. The adoption agency knew it was more likely disabled parents would adopt a disabled child, but also believed it was better for successful blind parents to raise a blind child rather than sighted parents who are unfamiliar with blind culture and accommodations.

Growing up, my parents were wonderful advocates for me. They worked with the school district to include braille lessons within my education, and they made sure I got equal treatment through accommodations and an IEP. My parents were advocates outside of the blind space as well. They made sure I received extra attention when dyslexia became present in my life; they brought my sister and I to Korean culture camp to ensure we got a taste of our ethnicity, and they made sure my pediatrician was comparing my growth statistics to Korean charts and not just American ones.

As I got older and my clinical depression began to appear in my teen years, my parents brought me to therapy and worked with my doctor to try to find a successful medication option. Most importantly, my parents taught me to be an advocate for myself. My first memory of this outside of school was disclosing my disability and asking for accommodations at my very first job, which was working at McDonalds.

As I transitioned into my young adult years and into college, I quickly realized how privileged I was to have already obtained the skills and confidence needed to advocate for myself. Not surprisingly, I was drawn to the Social Justice major at my small private liberal arts university. College was the first time I took a deep dive into my identities and how they shaped me. I recognized that my race was not just the color of my skin, and that my disability, invisible or visible, was valid whether other people saw it or not. I found that I could be valued and confident in all my identities, but still know that I am not defined by any one of them.

My second semester I took a global health class, which opened the door to public health. I was drawn to the variation in health systems and inequities across the globe. I remember stumbling across a quote in my textbook from Dan Beauchamp’s essay titled Public Health As Social Justice. From that point on I began finding numerous connections between my social justice and public health courses. I realized I could follow my passion of solving injustices through the means of public health to create social change. Thus arose my second major – Public Health Sciences.

The policy aspect of my career didn’t come as smoothly. If you would have told my freshmen year self that I’d be working in policy I would have never believed you. However, the summer following that first year I received the opportunity to intern in Baltimore for the National Federation of the Blind.

This internship was working throughout the various departments of a national nonprofit; to my surprise the first department we worked with was the Advocacy and Policy team, where they sped taught us about disability rights policy and then brought us to DC to speak with congressional offices. I felt powerful walking through the halls of congress knowing that this is where change starts. This was when my excitement and hidden skills of policy advocacy presented themselves. I saw that policy can be an effective and direct avenue to making change.

Over the next few years, I continued to seek internships and opportunities to expand my knowledge in public health policy. Whether it was through experiences interning with the American Association of People with Disabilities, a county level public health department, a state-based health plan, or for the office of Senator Amy Klobuchar, I knew I had found my purpose.

I completed graduate work at the University of Minnesota School of Public Health to receive my Masters’ Degree in Public Health Administration and Policy. I had a desire to learn more of the background policy analysis, research, and economics of health policy. Fortunately, through my academic advisor Ezra Golberstein, I was introduced to Andy Slavitt, and United States of Care (USofCare).

I interned with USofCare for my last year of graduate school before being hired full time. I was immediately inspired by our mission and vision; more specifically I was really attracted to the non-partisan aspect of the organization. It has been clear to me that more often than not everyone wants the same result— for everybody to have easy access, affordability, and trust within our health system.

However, I know we still have a long way to go because I still experience poor health care. In graduate school I went to a doctor who, once I disclosed my blindness to, no longer treated me like a competent person, but treated me like an object. She grabbed my arm and pulled me over to the exam table, where she continued to move my body in any way she wanted with no warning or consent. She assumed a blind person could not take direction to be examined properly, and decided it was within her authority to do whatever she wanted with my body, as a body and not as a person. This made me feel inferior, harassed, and distrusting of the health care system. It is very clear that there’s a problem when someone who was literally working on their MPH and knows the benefits of preventive and regular care has these feelings and refused to see any provider for well over a year. My experience is not rare either. I see all over social media and hear from my friends with disabilities having similar experiences with doctors.

This is why I am working for an organization that is fighting for the same passions I have. I am excited to be working with, and endlessly learning from, some of the smartest folks I know. This organization doesn’t just allow me to bring all of my lived experiences and hats to my work, but they encourage and want me to.

All of these experiences have helped to shape my vision for a better system, and that vision looks like this – that everyone will feel safe, dignified, and trusting of their providers. That we all will have access to health care whether that be financially, proximally, or physically knowing equipment will be accommodating for our individual bodies. That we can all feel like our doctors and our policymakers are advocating for us, and that we feel listened-enough to to advocate for ourselves.

#VoicesOfRealLife

As a part of our ongoing #VoicesOfRealLife series, we are connecting with folks across the country to share how COVID-19 is impacting their lives, their work, and their communities.

Hear from our very own Catherine Jacobson about our work and her experience navigating this pandemic with a visual disability.